Experts are concerned that the incidence of domestic and family violence will increase due to the COVID-19 restrictions, but the statistic are already shocking.

In Australia, domestic and family violence is against the law. A person who commits these crimes, can go to jail, whether they are a man or a woman.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s report, “Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018” shows that violence occurs across all ages and all socio-economic and demographic groups, but predominantly affects women and children. One in 4-6 women, since the age of 15, has experienced emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse by a current or former partner; while one in 6-20 men, since the age of 15, has experienced emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse by a current or former partner.

From 2012–13 to 2013–14, about 1 woman a week and 1 man a month were killed as a result of violence from a current or previous partner (Bryant & Bricknell 2017).

Some groups of people are at greater risk of family, domestic and sexual violence, particularly Indigenous women, young women, pregnant women, women separating from their partners, women with disability and women experiencing financial hardship. Women and men who experienced abuse or witnessed domestic violence as children (before the age of 15) are also at increased risk.

Nearly 2.1 million women and men witnessed violence towards their mother by a partner, and nearly 820,000 witnessed violence towards their father, before the age of 15. People who, as children, witnessed partner violence against their parents were 2–4 times as likely to experience partner violence themselves (as adults) as people who had not (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017).

What is Domestic and Family Violence?

Domestic and family violence includes behaviour or threats that aim to control a male or female partner by causing fear or threatening their safety. Domestic and family violence can include:

- Hitting, slapping, being kicked, being hit with a fist or other item (weapon), being dragged by clothing or hair, for example;

- Pushing, shoving;

- having something thrown at you that could hurt you;

- being burnt on purpose (eg, with a cigarette, a lighter/matches, an iron, stove top);

- choking;

- sexual assault such as being forced to have intercourse when you didn’t want to or because you were afraid of what your partner would do if you said no, being forced to do something sexual that you found to be humiliating or degrading, being forced to watch pornography when you didn’t want to, being forced by your partner to have sex with someone else (other than your partner);

- threats to harm;

- denying essential money to the partner or family;

- isolating the partner from friends and family;

- insulting or constantly criticising the partner; and/or

- threatening children or pets.

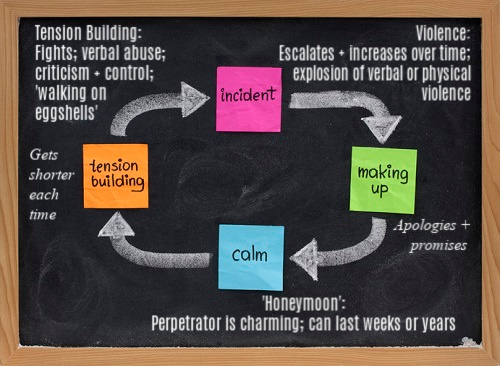

Domestic and family violence is often cyclic and the well-known process is represented by the Cycle of Violence diagram below.

People who experience domestic and family violence can often identify this cycle within their relationship.

Children at Risk

The risk to children of domestic and family violence is significant.

People who abuse their partners are highly likely to also assault their children. Pagelow (1989) found that at least half of all violent partners (most often men) also assault their children. The more severe the abuse of the partner, the worse the child abuse (Bowker, Arbitell, and McFerron, 1988).

Bowker, Arbitell, and McFerron (1988) also found that abuse of children is also more likely when the relationship is dissolving or the couple has separated. This is especially the case where the abusive partner is highly committed to continued dominance of their former partner and children. It is well-known that the time following separation is often the most dangerous time for the partner and children.

This is due to the fact that the abuse is directed at subjugating, controlling, and isolating. When an abused partner has separated from their abuser and is seeking to establish autonomy and independence, the abuser’s struggle to control and dominate may increase and may turn to abuse and subjugation of the children as a tactic of dominance and control of their mother (Stark and Flitcraft, 1988; Bowker, Arbitell, and McFerron, 1988).

Abusers often harm children as a punishment for their former partner for daring to leave them. Abusive partners often use custodial access to the children as a tool to terrorize their former partners or to retaliate for separation. Custodial interference is one of the few abusive tactics available to an abuser after separation; thus, it is not surprising that it is used extensively.

Hilberman and Munson (1977-78), found that older children are frequently assaulted when they intervene to defend or protect their mothers, with daughters more likely than sons to become victims of the abusive husband (Dobash and Dobash, 1979).

Abuse of the female partner is also the context for sexual abuse of female children. Where the mother is assaulted by the father, daughters are exposed to a risk of sexual abuse 6.51 times greater than girls in non-abusive families (Bowker, Arbitell, and McFerron, 1988).

Where a male is the perpetrator of child abuse, one study demonstrated that there is a 70 percent chance that any injury to the child will be severe and 80 percent of child fatalities within the family are attributable to fathers or father surrogates, such as step-fathers or mother’s boyfriends or de facto partners. (Bergman, Larsen, and Mueller, 1986).

In her article, “Assessing Whether Batterers Will Kill” (1990), Hart outlined that the likelihood of homicide is greater where the following factors are present:

- Threats of homicide or suicide. The abuser who has threatened to kill himself, his partner, the children or her relatives must be considered extremely dangerous.

- Fantasies of homicide or suicide. The more the abuser has developed a fantasy about who, how, when, and/or where to kill, the more dangerous he may be. The abuser who has previously acted out part of a homicide or suicide fantasy may be invested in killing as a viable “solution” to his problems. As in suicide assessment, the more detailed the plan and the more available the method, the greater the risk.

- Weapons. Where an abuser possesses weapons and has used them or has threatened to use them in the past in his assaults on the abused woman, the children or himself, his access to those weapons increases his potential for lethal assault. The use of guns is a strong predictor of homicide. If an abuser has a history of arson or the threat of arson, fire should be considered a weapon.

- “Ownership” of the abused partner. The abuser who says “Death before Divorce!” or “You belong to me and will never belong to another!” may be stating his fundamental belief that the woman has no right to life separate from him. An abuser who believes he is absolutely entitled to his female partner, her services, her obedience and her loyalty, no matter what, is likely to be life-endangering.

- Centrality of the partner. A man who idolizes his female partner, or who depends heavily on her to organize and sustain his life, or who has isolated himself from all other community, may retaliate against a partner who decides to end the relationship. He rationalizes that her “betrayal” justifies his lethal retaliation.

- Separation Violence. When an abuser believes that he is about to lose his partner, if he can’t envision life without her or if the separation causes him great despair or rage, he may choose to kill.

- Depression. Where an abuser has been acutely depressed and sees little hope for moving beyond the depression, he may be a candidate for homicide and suicide. Research shows that many men who are hospitalized for depression have homicidal fantasies directed at family members.

- Access to the abused woman and/or to family members. If the abuser cannot find her, he cannot kill her. If he does not have access to the children, he cannot use them as a means of access to the abused woman. Careful safety planning and police assistance are required for those times when contact is required, e.g. court appearances and custody exchanges.

- Repeated outreach to law enforcement. Partner or spousal homicide almost always occurs in a context of historical violence. Prior calls to the police indicate elevated risk of life-threatening conduct. The more calls, the greater the potential danger.

- Escalation of abuser risk. A less obvious indicator of increasing danger may be the sharp escalation of personal risk undertaken by an abuser; when an abuser begins to act without regard to the legal or social consequences that previously constrained his violence, chances of lethal assault increase significantly.

- Hostage-taking. A hostage-taker is at high risk of inflicting homicide. Between 75% and 90% of all hostage takings are related to domestic violence situations.

Everyone has the right to live free from violence, in a happy relationship and community. People do not have to accept being treated badly or harmed.

Author: Merryl Gee, BSocWk, AMHSW, MAASW, MACSW, MANZMHA, MPACFA.

Author: Merryl Gee, BSocWk, AMHSW, MAASW, MACSW, MANZMHA, MPACFA.

Merryl Gee is a psychotherapist working from a strengths-based, person-centred framework. With over 30 years’ experience, she has a particular interest people who have experienced trauma such as sexual assault or childhood sexual abuse.

To make an appointment with Brisbane Psychotherapist Merryl Gee try Online Booking. Alternatively, you can call M1 Psychology Loganholme on (07) 3067 9129 or Vision Psychology Wishart on (07) 3088 5422 .

References:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017) Personal Safety Survey 2016. ABS cat. no. 4906.0. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018.

- Bergman, A., Larsen, R.M., and Mueller, B. (1986). “Changing spectrum of Serious Child Abuse.”

Pediatrics, 77 (1). - Bowker, L.H., Arbitell, M., & McFerron, J. R. (1988). “On the Relationship Between Wife Beating and Child Abuse.” In K. Yllo and M. Bograd (Eds.), Perspectives on Wife Abuse. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage. - Bryant & Bricknell (2017) Homicide in Australia 2012–13 to 2013–14: National Homicide Monitoring Program Report. Canberra: AIC.

- Department of Child Protection, Western Australia (2015) Fact Sheet 2: Indicators of family and domestic violence Retrieved 26-04-2020 from https://www.dcp.wa.gov.au/CrisisAndEmergency/FDV/Documents/2015/Factsheet2Indicatorsoffamilyanddomesticviolence.pdf

- Dobash, R. E. & Dobash, R. P. (1979). Violence Against Wives. New York: Free Press.

- Hart, Barbera J. (1992) “Children of Domestic Violence: Risks and Remedies” in Minnesota Centre Against Violence and Abuse, Barbera J. Hart’s Collected Writings Pp 12-17.

- Hart, Barbera J. (1990) “Assessing Whether Batterers Will Kill” in Minnesota Centre Against Violence and Abuse, Barbera J. Hart’s Collected Writings Pp 1-2.

- Hilberman, E. and Munson, K. (1977-78). “Sixty Battered Women.” Victimology: An International Journal, 2 (3-4).

- Jaffe, P., Wolfe, D.W., & Wilson, S. (1990). Children of Battered Women: Issues in Child Development and Intervention Planning. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Pagelow, M. (1989). “The Forgotten Victims: Children of Domestic Violence.” Paper prepared for presentation at the Domestic Violence Seminar of the Los Angeles County Domestic Violence Council.

- Rosenbaum, A. and O’Leary, K.D. (1981). “Children: The Unintended Victims of Marital Violence.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 5 (14).

- Stark, E. & Flitcraft, A. (1988). “Women and Children at Risk: A Feminist Perspective on Child Abuse.” International Journal of Health Services, 18, (1), 97-118.

- Walker, L. E. (1984). The Battered Woman Syndrome. Springer.

- Wallerstein, J.S. and Kelly, J.B. (1980). Surviving the Breakup: How Children and Parents Cope with Divorce. New York: Basic Books.