Service providers, such as GPs, psychologists, psychotherapists and counsellors, play a pivotal role in identifying and responding to domestic and family violence.

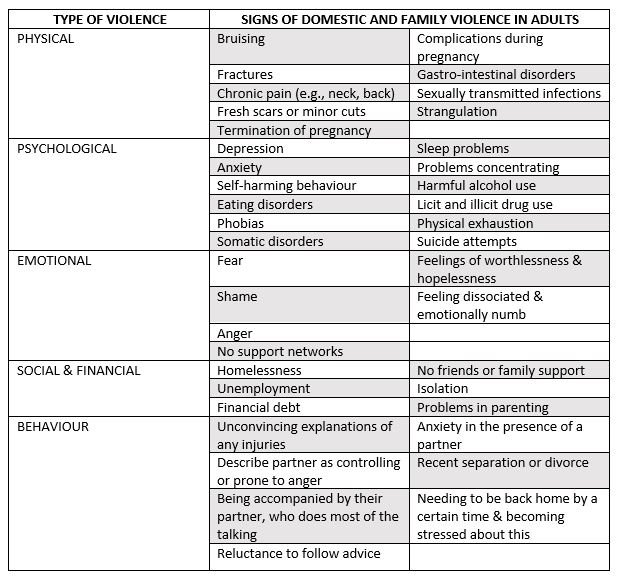

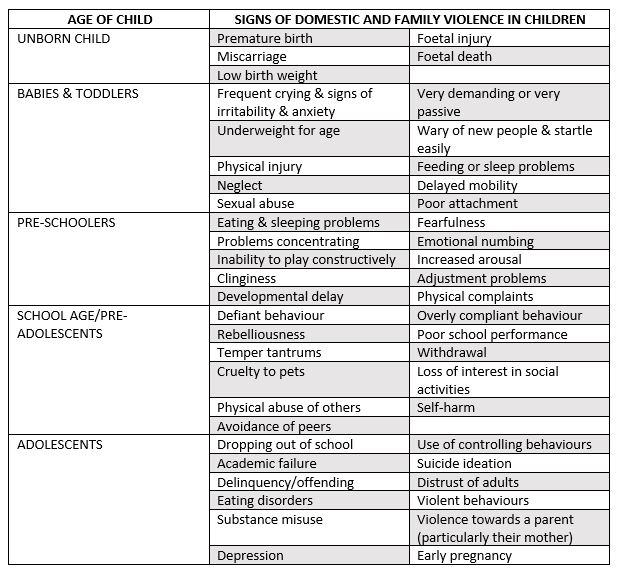

The lists of possible indicators of family and domestic violence (see Tables below) are provided in relation to adult and child victims for the purpose of forming professional judgements about when to undertake family and domestic violence screening.

Indicators can often be attributed to causes other than violence, be overlooked or disregarded. However, it is essential that service providers initiate a conversation about family and domestic violence if a number of indicators or a pattern of recurring indicators are present. This process should be guided by a specific domestic violence screening tool (like this one), or other similar prompting questions.

Indicators of Domestic and Family Violence in Adults

Indicators of Family and Domestic Violence in Children

Exposure to family and domestic violence can affect all aspects of a child’s health and wellbeing including their physical health and safety, emotional, behavioural and social development and wellbeing. These impacts directly relate to what may be observed as an indicator. A list of possible indicators of a child who is experiencing domestic and family violence in their home, is provided in the following table.

The majority of children from violent homes observe the violence inflicted by their fathers upon their mothers; most research suggests as many as 90 percent of children from violent homes witness their fathers battering their mothers (Pagelow, 1990; Walker, 1984).

One study demonstrated that some fathers deliberately arrange for the children to witness the violence (Dobash and Dobash, 1979), and other empirical work suggests that the violence occurs only when the children are present (Wallerstein and Kelly, 1980).

Children witnessing the violence inflicted on their mothers, evidence behavioural, somatic, or emotional problems similar to those experienced by physically abused children (Jaffe, Wolfe, and Wilson, 1990). Boys often become aggressive, fighting with siblings and schoolmates and having temper tantrums. Girls are more likely to become passive, clinging, and withdrawn (Hilberman and Munson, 1977-78). Male children who witness the abuse of mothers by fathers are more likely to become men who abuse in adulthood than those male children from homes free of violence (Rosenbaum and O’Leary, 1981).

Everyone has the right to live free from violence, in a happy relationship and community. People of any age do not have to accept being treated badly or harmed.

Author: Merryl Gee, BSocWk, AMHSW, MAASW, MACSW, MANZMHA, MPACFA.

Author: Merryl Gee, BSocWk, AMHSW, MAASW, MACSW, MANZMHA, MPACFA.

Merryl Gee is a psychotherapist working from a strengths-based, person-centred framework. With over 30 years’ experience, she has a particular interest people who have experienced trauma such as sexual assault or childhood sexual abuse.

To make an appointment with Brisbane Psychotherapist Merryl Gee try Online Booking. Alternatively, you can call M1 Psychology Loganholme on (07) 3067 9129 or Vision Psychology Wishart on (07) 3088 5422 .

References:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017) Personal Safety Survey 2016. ABS cat. no. 4906.0. Canberra: ABS.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2018) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018

- Bergman, A., Larsen, R.M., and Mueller, B. (1986). “Changing spectrum of Serious Child Abuse.” Pediatrics, 77 (1).

- Bowker, L.H., Arbitell, M., & McFerron, J. R. (1988). “On the Relationship Between Wife Beating and Child Abuse.” In K. Yllo and M. Bograd (Eds.), Perspectives on Wife Abuse. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage. - Bryant & Bricknell (2017) Homicide in Australia 2012–13 to 2013–14: National Homicide Monitoring Program Report. Canberra: AIC.

- Department of Child Protection, Western Australia (2015) Fact Sheet 2: Indicators of family and domestic violence Retrieved 26-04-2020 from https://www.dcp.wa.gov.au/CrisisAndEmergency/FDV/Documents/2015/Factsheet2Indicatorsoffamilyanddomesticviolence.pdf

- Dobash, R. E. & Dobash, R. P. (1979). Violence Against Wives. New York: Free Press.

- Hart, Barbera J. (1992) “Children of Domestic Violence: Risks and Remedies” in Minnesota Centre Against Violence and Abuse, Barbera J. Hart’s Collected Writings Pp 12-17

- Hart, Barbera J. (1990) “Assessing Whether Batterers Will Kill” in Minnesota Centre Against Violence and Abuse, Barbera J. Hart’s Collected Writings Pp 1-2

- Hilberman, E. and Munson, K. (1977-78). “Sixty Battered Women.” Victimology: An International Journal, 2 (3-4).

- Jaffe, P., Wolfe, D.W., & Wilson, S. (1990). Children of Battered Women: Issues in Child Development and Intervention Planning. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Pagelow, M. (1989). “The Forgotten Victims: Children of Domestic Violence.” Paper prepared for presentation at the Domestic Violence Seminar of the Los Angeles County Domestic Violence Council.

- Rosenbaum, A. and O’Leary, K.D. (1981). “Children: The Unintended Victims of Marital Violence.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 5 (14).

- Stark, E. & Flitcraft, A. (1988). “Women and Children at Risk: A Feminist Perspective on Child Abuse.” International Journal of Health Services, 18, (1), 97-118.

- Walker, L. E. (1984). The Battered Woman Syndrome. Springer.

- Wallerstein, J.S. and Kelly, J.B. (1980). Surviving the Breakup: How Children and Parents Cope with Divorce. New York: Basic Books.